The sound of him was always unmistakable. To many, and surely to most Americans beyond a certain age, his voice was one of the few verities of popular entertainment. It seemed to dance out as irresistibly as a whimsical sigh of relief, full of fluid and breezy resonances perfectly suited to the fragile and often sticky sentiments of the romantic era that swept him to superstardom. His way of crooning was, as well, exactly attuned to the easygoing personality he projected onstage and in most of his 60 movies. His style was so relaxed -- almost sleepy -- that it was hard to remember he won an Oscar for skillful acting as a priest in Going My Way (1944). Only at golf, which he often appeared to take more seriously than his career, did he ever publicly show tension. Indeed, when Bing Crosby died of a heart attack at 74 last week, nobody who knew him well could be surprised that the end came on the links.

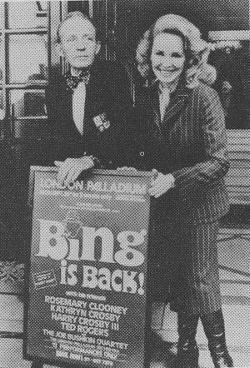

Crosby collapsed after carding an 85 on the suburban La Moraleja Golf Club on the outskirts of Madrid. Only the day before, he had arrived in Spain from England after a successful tour climaxed by a sellout performance at London's Palladium. The tour, he told reporters in Madrid, had been a reassuring test of his recovery from the back injury he got last March when he fell from the stage in Pasadena, Calif., during a celebration of his 50th year in show business.

Crosby collapsed after carding an 85 on the suburban La Moraleja Golf Club on the outskirts of Madrid. Only the day before, he had arrived in Spain from England after a successful tour climaxed by a sellout performance at London's Palladium. The tour, he told reporters in Madrid, had been a reassuring test of his recovery from the back injury he got last March when he fell from the stage in Pasadena, Calif., during a celebration of his 50th year in show business.

Crosby will of course sing on and on. And not just in records of White Christmas, the tinselly ballad that Crosby, with the help of World War II's general homesickness, transformed into a national holiday anthem. Echoes of Crosby's voice have passed into the style of every important prerock balladeer in the U.S. Long before his personal style was submerged by Elvis Presley and all his musical progeny, Crosby had become not only one of the world's richest entertainers, worth tens of millions, but perhaps the most influential pop singer of his time. Last week Frank Sinatra was one of a troupe of show-biz giants who affirmed not merely their sorrow but Crosby's enduring significance. Said Sinatra: "He was the father of my career, the idol of my youth and a dear friend of my maturity. Bing leaves a gaping hole in our music and in the lives of everybody who loved him. And that's just about everybody."

True. Not the least remarkable aspect of Crosby's career was that once it waxed big in the early 1930s, it never waned. He aroused unusual affection in his public. Bing outstripped both General Dwight Eisenhower and President Harry Truman in one popularity poll of the late 1940s. Any one of a variety of casual nicknames -- Der Bingle, Old Dad, the Groaner -- was enough to identify him in a newspaper headline. In a cartoon his image could be evoked with merely a nonchalant tilted smile, or by one of the pipes or hats or gaudy sports shirts he affected as part of a studiously insouciant manner.

True. Not the least remarkable aspect of Crosby's career was that once it waxed big in the early 1930s, it never waned. He aroused unusual affection in his public. Bing outstripped both General Dwight Eisenhower and President Harry Truman in one popularity poll of the late 1940s. Any one of a variety of casual nicknames -- Der Bingle, Old Dad, the Groaner -- was enough to identify him in a newspaper headline. In a cartoon his image could be evoked with merely a nonchalant tilted smile, or by one of the pipes or hats or gaudy sports shirts he affected as part of a studiously insouciant manner.

Many of the names got pinned on him by his pal Bob Hope. Crosby and Hope became linked by the sequence of seven Road pictures made with Dorothy Lamour. Indeed, they were coupled ever after the very first in 1940, The Road to Singapore. Bing and Bob were frequently engaged onstage in a gibing dialogue that was itself like the soft shoe they also did together -- once while singing, hands joined, Mairzy Doats. "People will think we're in love," Crosby sang to a throng of troops during World War II -- and worked in the line, "Don't laugh at Hope's jokes so much." Out popped Hope, barbing: "Keep crooning, Bing, you make a great target."

The Road shows were rummage sales of stuff out of vaudeville, burlesque -- marvelously shoddy masterpieces of farce and fantasy, stitched together with cliches and ad libs. The series proved, if nothing else, that Crosby was nearly as deft a comedian as Hope. But by then Bing was a giant with or without Hope.

The Road to Bingdom began in 1903, in Tacoma, Washington. Bing was the son of a devout Roman Catholic. His real name, Harry Lillis Crosby, refused to stick. According to one legend, he so loved a comic strip called the Bingville Bugle that he became Bing himself. He also became a dedicated sportsman (football, baseball, fishing), a good singer in a house full of singing, and a conspicuous truant. He nevertheless went to Gonzaga University in Spokane as a law student. The only useful part of the course, which ended with his first amateur musical success, was public speaking. Said he, "I owe all to elocution."

Wide recognition came after a few years of modest success as one of the Rhythm Boys featured by Paul Whiteman -- this before the King of Jazz fired him for not taking his work seriously enough. Nor was Whiteman the only early employer that Crosby disenchanted by drinking and carousing too much. He became a national name only after a medical fluke -- the sudden occurrence of nodules on his vocal cords -- caused him to lose his voice just before his first scheduled radio network show in 1931. When the voice came back, it had, thanks to the nodules, what Crosby called "the effect of a lad with his voice changing singing into a rain barrel."

The effect was just what the Crosby sound needed. In earlier work he sang with much jazzier effects. An artist in search of a personal style, he listened hard to Al Jolson, Mildred Bailey and Louis Armstrong. Finally Bing developed that mellifluous tone, a mere phrase of which causes millions of Americans to imagine the gold of the day meeting the blue of the night. Here was the voice that has sold more records than any other on earth save that of Elvis.

There was also the voice, suddenly made famous on radio, that inspired Hollywood to cast Crosby in the feature picture (Paramount's) The Big Broadcast that was to launch the flip side of Bing's career. In the movies as onstage, Crosby seemed always to come on singing happy, upbeat, don't-worry songs that the trouble-weary public loved during the Depression. He scored successees in such movies as Pennies from Heaven and Waikiki Wedding, but it was as the lazy, goodhearted ne'er-do-well in Sing You Sinners, in 1938, that he found the casual acting mode the public relished.

Crosby's biggest critical success was Country Girl, but his personal favorite among his movies was High Society (1956). It found him singing and dancing with Frank Sinatra at an "elegant swellegant" party and playing a concertina and crooning True Love, as only the first crooner could croon, to not-yet-royal Grace Kelly. Unlike many stars, Crosby surrounded himself with other big talents. He worked with Fred Astaire in Holiday Inn (in which he sang White Christmas), with Ethel Barrymore in Just for You and with Ingrid Bergman in Bells of St. Mary's.

It may be absurd to attribute modesty to anyone in the egomaniacal world of show biz. Yet a certain diffidence adhered to Crosby even as a celebrity. In his artistry, he owned the natural jazzman's gift of blending with, rather than blaring against, an ensemble of fellow performers -- a knack never used better than in the scatty and mellow duets (Gone Fishin, for one) that he recorded with Armstrong. A similar trait made his private life seem actually private in contrast to the typical Hollywood star's. He had his troubles, heartbreak at times in his first marriage to hard-drinking Dixie Lee, who died of cancer in 1952, and again in dealing with his four sons with a penchant for mischief. In 1957 he married Kathryn Grant, 30 years younger than he, and started another family. Crosby never claimed to be an exemplary singer or exemplary anything else, and once he attributed his good reputation to his practice of admitting his sins only to the "father confessor."

He had slowed down in recent years but had proclaimed an intent never to retire completely: "I'll keep singing as long as they'll have me." A grieving Bob Hope noted that the two old Roadsters, along with Dorothy Lamour, had just finished working up plans to try one more for the Road. The film, said Hope, was to be called The Road to the Fountain of Youth.

Crosby collapsed after carding an 85 on the suburban La Moraleja Golf Club on the outskirts of Madrid. Only the day before, he had arrived in Spain from England after a successful tour climaxed by a sellout performance at London's Palladium. The tour, he told reporters in Madrid, had been a reassuring test of his recovery from the back injury he got last March when he fell from the stage in Pasadena, Calif., during a celebration of his 50th year in show business.

Crosby collapsed after carding an 85 on the suburban La Moraleja Golf Club on the outskirts of Madrid. Only the day before, he had arrived in Spain from England after a successful tour climaxed by a sellout performance at London's Palladium. The tour, he told reporters in Madrid, had been a reassuring test of his recovery from the back injury he got last March when he fell from the stage in Pasadena, Calif., during a celebration of his 50th year in show business.

by Frank Trippett

by Frank Trippett True. Not the least remarkable aspect of Crosby's career was that once it waxed big in the early 1930s, it never waned. He aroused unusual affection in his public. Bing outstripped both General Dwight Eisenhower and President Harry Truman in one popularity poll of the late 1940s. Any one of a variety of casual nicknames -- Der Bingle, Old Dad, the Groaner -- was enough to identify him in a newspaper headline. In a cartoon his image could be evoked with merely a nonchalant tilted smile, or by one of the pipes or hats or gaudy sports shirts he affected as part of a studiously insouciant manner.

True. Not the least remarkable aspect of Crosby's career was that once it waxed big in the early 1930s, it never waned. He aroused unusual affection in his public. Bing outstripped both General Dwight Eisenhower and President Harry Truman in one popularity poll of the late 1940s. Any one of a variety of casual nicknames -- Der Bingle, Old Dad, the Groaner -- was enough to identify him in a newspaper headline. In a cartoon his image could be evoked with merely a nonchalant tilted smile, or by one of the pipes or hats or gaudy sports shirts he affected as part of a studiously insouciant manner.