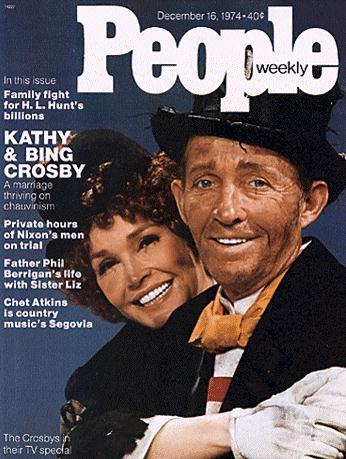

Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of triteness keeps TV's Christmas specials from their appointed rounds of carols. The most established of them all had to overcome 100 degree temperatures at its L.A. taping last month, along with the other traditional indignities. The star was swaddled in a scratchy Santa suit. The cue cards were flipped through the Iyrics of "White Christmas," which, in this case, was especially ridiculous (except perhaps to the idiot-card union) -- this was the ancient, annual Bing Crosby family special. Counting radio, it has spanned 38 seasons and two Crosby families (not to mention helping Bing's rendition of "White Christmas" become probably the biggest-selling single -- over 30 million -- in the history of records).

This year again, only Crosby's three younger kids (13 to 16) and their mother, Kathryn Grant, performed in the show. But the four older prodigal sons (now 36 to 41) by his late wife, Dixie Lee, made a point of visiting the set. It was a tribute to the old man, now 70, who for all his rigorous ten-hour days of taping, had nearly died last January of a rare lung fungus called nocardia.

The resulting special, to be aired Dec. 15 over NBC, shows no ill effects -- it is, like earlier celebrations, as sugary, smooth and canned as Minute Maid O.J. If anything, Bing's ailment, having ended his smoking career, has made his baritone (says his veteran coproducer-writer Bill Angelos) "better and more mellow than it's been in years." Any jottings on the Crosby family Christmas card might also note a new mellowness in Kathryn in the past year. At 41, she has just premiered a new morning TV interview show in San Francisco and continues to moonlight with the accomplished local American Conservatory Theatre. She is clearly a more self-assured and fulfilled woman than when she married Bing -- a 24-year-old ex-Texas beauty queen and Columbia Pictures starlet. For years she thrashed around trying to express herself as a registered nurse and then as a schoolteacher.

In any case, the fondness within the family which suffuses next Sunday's hour is no put-on for the TV public. Kathryn now has developed a personally satisfying modus vivendi with the congenital, if gentle, chauvinism of her sportsman husband's endless summer. His record royalties (he has sold more than 400 million), his broadcasting and production holdings, his race horses, his 25 percent piece of the Pittsburgh Pirates et al, now take care of themselves. So Bing is free to focus on pleasure and to enjoy a seasonal cycle that includes fall duck-shooting in northern California or Chesapeake Bay. Then perhaps, it's off to Africa, but for camera safaris only. "I'm not interested in big game," he says, and he now shoots only "for the table." In May, he heads for his hacienda in Las Cruces in Baja California, Mexico, and fishing in the Sea of Cortez. "For a while I was going for a world record in marlin, but that got beyond my reach," Bing confesses. Besides, adds conservationist convert Crosby, "We now release marlin after we catch them -- they're an endangered species." In between, he golfs daily where the sun is -- if not at home in Hillsborough, Calif. (where the Hearsts also live), then in the British Isles or on the Continent. He has just acquired a second Mexican home in Guadalajara, because it has "the very best climate in the world for a golfer." Many of his sportive escapades through the years have been stag with old showbiz cronies like Phil Harris, staged in some instances for ABC's "American Sportsman" series.

So where does all that leave his family? "We used to be able to take the kids out of school," explains Bing. "Their mother would teach them. But now two are in high school, and it isn't allowed." As for Kathryn herself, "Someone once criticized me," she says, "for not being down at Las Cruces when Bing was there. I told them Bing hadn't invited me. And when he did invite me, I would go." Which is why she finds her new TV job "fits a lot of my needs. We can tape ahead for times when Bing wants to be away." Kathryn also makes practical use of her old nurse's training. She vaccinates the local kids in Las Cruces and gives annual flu shots to her colleagues in the ACT repertory company.

She is also active in Bay Area charities, helps plan the annual Bing Crosby benefit golf tourney, studies voice and dance, and jogs five miles a day, memorizing poems like Omar Khayyam's "Rubaiyat on the run." "I don't think kids today want a mother waiting at home with a cookie and milk," she says.

Their 16-year-old, Harry Lillis Jr., "is a serious music student" at a Jesuit high school. He duck hunts with Dad, teaches guitar and, like a true Californian, is into oenology ("We've always allowed the children to toast in wine on special occasions," says Mom). Mary Frances is the famous first and only Crosby daughter, a hazel-eyed knockout who studies ballet four or five hours a day and, says Kathryn, "can relate to people on an adult level sometimes and be very babyish at others, which is nice in a 15-year-old." The youngest, Nathaniel, Mom beams, is "cool, very self-contained and organized," the junior jock in the clan. Already, at 13, he can out-drive his father in golf.

But Bing, his illness last winter notwithstanding, still has the complete game, and can wipe out Nat on the final card. It is a skill he has sharpened as an escapee from smoggy L.A. to Hillsborough a decade ago. Nor is Bing an aficionado of the indoor sporting life of places like Vegas. His preference for the great outdoors has assured that whatever the flacks may say about the return of Sinatra, ol' Bing Crosby still has the clearest, bluest eyes in the West.