Written 2003 by Steven Lewis

Joan Caulfield was an unknown 22-year-old actress when she got the call in 1945 to play the leading lady in Bing Crosby's motion picture Blue Skies. Mark Sandrich, who was preparing to produce and direct the movie, discovered Caulfield in the rushes of her first Paramount movie, Miss Susie Slagle's. He was so impressed by her beauty that he wanted to cast her as a song-and-dance star in the Crosby musical -- if Joan could dance. Joan let her enthusiasm overwhelm her honesty and assured Sandrich she could indeed dance. She couldn't. Sandrich sent her to Carmalita Maracci's dance school at her own expense in the hope that her role could be salvaged.

Sandrich died suddenly of a heart attack on March 4, 1945, at the age of 44, before filming could begin. His replacements were much less sympathetic toward Joan, especially since Crosby's co-star and choreographer, tap-dancer Paul Draper, also wanted Joan out. He did not want a leading lady with two left feet, even if they were pretty feet. Joan's name disappeared from the cast sheets and press releases. Meanwhile, Draper began auditioning other actresses for Joan's part.

Then, suddenly, Joan was reinstated, Draper was fired, the script was rewritten and Fred Astaire was coaxed out of retirement to replace Draper. Why were these extraordinary steps taken for an unknown actress? (Joan's first movie, Miss Susie Slagle's, would not be released until 1946.) Obviously, someone very powerful had taken an interest in Joan and was determined to keep her in that movie. That someone most likely was Bing Crosby, who had just won the Oscar for his role as Father O'Malley in Going My Way. Not only was he Hollywood's leading box-office attraction, Bing was also a major stockholder in Paramount.

Joan met Bing as she was preparing for her first starring film role in "Miss Susie Slagle's." She was invited to visit the set of "Here Come the Waves" to watch Bing perform in June 1944. Bing was immediately smitten and the two were soon discreetly dating. Even Bing's 2-month USO tour of Europe that summer did not dampen his flame for Joan, for when he returned to the States he visited Joan at her home. Their first time working together was to record the radio version of Bing's movie Sing You Sinners for the Lux Radio Theatre on April 6, 1945.

In November 1945 Bing traveled to New York City where he spent most of the next 10 weeks. Joan Caulfield's family also lived in New York City near Bing's hotel. There Bing attracted the attention of 2 celebrity stalkers, sisters Violet and Mary Barsa. Wherever Bing went, they followed, even if it meant bribing the gatekeepers. The sisters kept a diary of Bing's activities, their interaction with him and who he was with. Years later Gary Giddins, Bing's biographer, befriended one of the sisters and gained access to their diary. The diary documented in detail that Bing's lengthy visit to New York was in large part to share precious moments with Joan.

Rumors of Bing's affair with Joan caught the attention of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, who confronted Bing with the rumors. Bing responded to Hedda in writing: "She [Joan] is in New York and there is so much to be seen and done here but not much fun solo. I'm a good friend of her family and I've been a guest at their house on many occasions when they've been entertaining mutual friends. Believe me, Hedda, there is nothing clandestine about this situation and I have nothing to be ashamed of or circumspect about." (Giddins, Swinging on a Star, p565)

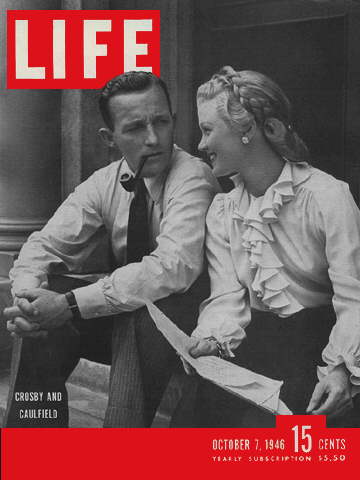

Bing's affair with Joan continued throughout 1946. Neither Blue Skies nor Miss Susie Slagle's had been released when Paramount announced that Bing's next movie, Welcome Stranger, would also co-star Caulfield. In 1954 Joan admitted to a relationship with a "top film star" who was also a married man with children who eventually chose his wife and children over her.

That this "top film star" was Bing Crosby was confirmed by actress Patricia Neal, who shared a cruise ship to England with Caulfield in 1948. At the time Neal was having her own affair with a much older married actor, Bing's friend Gary Cooper. Like Bing, Coop eventually decided to stay with his family too. Neal wrote:

She [Joan Caulfield] was a lovely girl and we had some good talks. She, too, was in love with an older married man who was quite as famous as Gary [Cooper]. She confided to me that she desperately wanted to marry Bing Crosby. We were in the same boat in more ways than one, but I could not tell her so." (Neal, As I Am, Simon and Schuster, 1988, p109)In his 1983 biography, Bing's son Gary reported overhearing some of Bing's friends who were visiting the Crosby home in 1950:

They were swapping yarns about the good old days, when one of them came up with a story that blew my head off. "Anyone remember the one about Bing and the cutie in the big picture hat? They were slinking out of someone's house about seven-thirty in the morning, all bleary-eyed from the night before, and just as they hit the front gate they're spotted by a civilian on his way to work. Well, the guy couldn't believe his eyes. He did a double take, slammed on his brakes and yelped, 'Father O'Malley?' and then sped off like the devil himself was after him."Bing requested permission from the Catholic hierarchy to divorce his wife, Dixie, so he could marry Caulfield. Catholic Church spokesmen that included Francis Spellman, archbishop of New York, told Bing that 'Father O'Malley' had become an important Catholic symbol and that he must not divorce Dixie. The devout Catholic in Bing respected their demands and remained with Dixie until her death in 1952. Bing stopped seeing Joan in 1948. In 1950 Joan married Hollywood producer Frank Ross. They divorced nine years later. She married her dentist in 1960. They divorced in 1966. She never remarried. Each marriage produced a son. Joan died of cancer on June 18, 1991.Everyone thought the anecdote was hilarious, but to my seventeen-year-old way of thinking it signaled the end of the universe.... Father O'Malley. That meant it was after Going My Way, and the good old days they were talking about weren't all that old. (Crosby, Going My Own Way, 143-44)