A History of Tin Pan Alley

Adapted from the book Tin Pan Alley by David Jasen

The history of Tin Pan Alley is a history of the United States as seen by its tunesmiths. We find an incredible variety of materials documented in songs which do, indeed, seem to have mirrored every aspect of American life from the beginning of Tin Pan Alley in the 1890s to the latest digital technology. We can chronicle the changing musical tastes of Americans, along with our social, economic and political concerns, by the kinds of popular music we bought, played and listened to -- from the tear-jerker to the latest rock song.

In an era before Elvis Presley made a song's performance more important than its publication, when a song's popularity was determined not by the number of records it sold but by the number of copies of sheet music it sold, Tin Pan Alley was the name given to the publishing business that hired composers and lyricists on a permanent basis to create popular songs. The publishers used extensive promotion campaigns to market these songs to the general public in sheet music form with attractive covers. Originally, Tin Pan Alley was a nickname given an actual street (West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue) in Manhattan where many of the fledgling popular music publishers had their offices. In time, it became the generic term for all publishers of popular American sheet music, regardless of their geographic locations.

In an era before Elvis Presley made a song's performance more important than its publication, when a song's popularity was determined not by the number of records it sold but by the number of copies of sheet music it sold, Tin Pan Alley was the name given to the publishing business that hired composers and lyricists on a permanent basis to create popular songs. The publishers used extensive promotion campaigns to market these songs to the general public in sheet music form with attractive covers. Originally, Tin Pan Alley was a nickname given an actual street (West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue) in Manhattan where many of the fledgling popular music publishers had their offices. In time, it became the generic term for all publishers of popular American sheet music, regardless of their geographic locations.

Today's approach to pop music is a far cry from the beginning of mass-marketed popular music, which started toward the end of the nineteenth century and ended in the middle 1950s. Throughout the Alley's 70 years, popular music was developed in a variety of forms -- love ballads, syncopated tunes, Latin American music, nonsense songs, show tunes -- and marketed for adults. The music was presented and promoted in sheet music form for voice and piano. The public was induced to purchase the music sheets when they saw and heard their favorite performers incorporate the songs into their acts, first in the theater and in vaudeville, then through recordings (first on cylinders, then on flat discs which rotated 78 times per minute), later on radio, then in films, and finally on television.

Before the 1890s such occupations as composer, lyricist and even publisher of popular music did not exist. This is not to say that popular songs were not written and published, but that nobody was hired expressly to compose and write them on demand. That demand came later, after the Alley was firmly established, either from the stars who wanted songs suited to their personalities or else from the publishers who demanded songs of a type which a rival publisher had and which the public was currently buying.

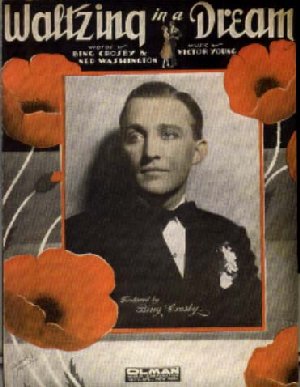

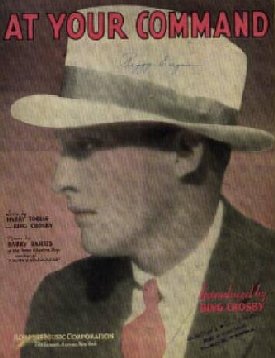

After the vaudeville era, when radio captured audiences, airtime became a precious commodity, and song pluggers (also known as "contact men") concentrated on those orchestra leaders and singers who had their own programs. Bing Crosby, for example, with regular exposure on both radio and in the movies, became the greatest plug a song could have in the 1930s. While getting the song recorded by as many performers as possible was desirable, the main thrust of plugging before the Presley era was to sell copies of sheet music.

Along with getting a star to use a song in the act or on the air, publishers discovered early in the history of Tin Pan Alley that the song's cover played a most important role in the selling of the popular music sheet. From the mid-1890s, publishers took great care with their covers. Sometimes a combination of photograph and illustration was used; sometimes a performer's photograph appeared on the cover. A performer's photograph on a cover served as an incentive for the performer to retain the song and to encourage fans of the performer to buy the sheet as a souvenir. Whatever the motivation, by the turn of the century cover art was a significant element in helping to sell copies of sheet music. Today these covers often comprise the only extant photographs of some of the places and people of this era, giving the covers added desirability, importance and value.

Along with getting a star to use a song in the act or on the air, publishers discovered early in the history of Tin Pan Alley that the song's cover played a most important role in the selling of the popular music sheet. From the mid-1890s, publishers took great care with their covers. Sometimes a combination of photograph and illustration was used; sometimes a performer's photograph appeared on the cover. A performer's photograph on a cover served as an incentive for the performer to retain the song and to encourage fans of the performer to buy the sheet as a souvenir. Whatever the motivation, by the turn of the century cover art was a significant element in helping to sell copies of sheet music. Today these covers often comprise the only extant photographs of some of the places and people of this era, giving the covers added desirability, importance and value.

The artwork of each era in Tin Pan Alley's history is distinctive. As many people collect sheet music today as collect postcards, posters and other works of popular art.

Among the important factors in the rise of Tin Pan Alley was the rapid growth of vaudeville. Theatres were constructed across the country in great numbers beginning in the 1890s. Names like Strand, Lyceum and Orpheum sprouted up in towns and villages everywhere. All were supplied talent by booking agencies such as William Morris and Keith-Albee, most of which were located in New York City.

Each year, before they set out to troop across the country, vaudeville performers would stop at publishing houses for songs they might use to freshen up their acts. For a star, staff composers and lyricists would create special material for exclusive use.

The record industry began to sell flat discs commercially in 1897. They were an invention of Emile Berliner, who also invented the gramophone on which to play them. Earlier, in 1877, Thomas Edison had invented his phonograph which played cylindrical records, but by 1908 the gramophone and its flat discs became the public's preferred machine and playback device. It wasn't until the 1920s that record sales enjoyed enough popularity to interest Tin Pan Alley. The record companies needed Tin Pan Alley's output, and Tin Pan Alley needed the additional plug capabilities of continual, permanent performances. The publishers also did not mind the two-cents-a-copy royalty given them by the record companies after the copyright law of 1909 was enacted. Not until after the Second World War would the record industry replace the Alley as the mainstay of the music business. With the coming of rock and roll, the transition was complete, and recorded performances became the most important aspect of popular music, rather than sales of the song itself.

Symbolically, Tin Pan Alley died on April 12, 1954, when Bill Haley (1925-81) and his Comets recorded Max Freedman and Jimmy De Knight's Rock Around the Clock. It had been published a year earlier and would not create a sensation until a year later, but Haley's recording for Decca would become the first international rock 'n' roll bestseller. By the time Elvis Presley recorded his first disc for RCA Victor, "Heartbreak Hotel," in January 1956, there was no doubt that the era of Tin Pan Alley was over. From that point on, the list of each year's Top Ten songs would be almost entirely composed of rock and roll numbers which were not sold to any great extent in sheet music form. Popular music, which had been originally created for adults who went to vaudeville shows, theatres, nightclubs and saloons and who bought sheet music to sing and play, became dominated by teenagers who valued the performance more than the written music and words.

Composers of Early American Pop Music

||| Crosby Sheet Music ||| BCIM Home Page

In an era before Elvis Presley made a song's performance more important than its publication, when a song's popularity was determined not by the number of records it sold but by the number of copies of sheet music it sold, Tin Pan Alley was the name given to the publishing business that hired composers and lyricists on a permanent basis to create popular songs. The publishers used extensive promotion campaigns to market these songs to the general public in sheet music form with attractive covers. Originally, Tin Pan Alley was a nickname given an actual street (West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue) in Manhattan where many of the fledgling popular music publishers had their offices. In time, it became the generic term for all publishers of popular American sheet music, regardless of their geographic locations.

In an era before Elvis Presley made a song's performance more important than its publication, when a song's popularity was determined not by the number of records it sold but by the number of copies of sheet music it sold, Tin Pan Alley was the name given to the publishing business that hired composers and lyricists on a permanent basis to create popular songs. The publishers used extensive promotion campaigns to market these songs to the general public in sheet music form with attractive covers. Originally, Tin Pan Alley was a nickname given an actual street (West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue) in Manhattan where many of the fledgling popular music publishers had their offices. In time, it became the generic term for all publishers of popular American sheet music, regardless of their geographic locations.

Along with getting a star to use a song in the act or on the air, publishers discovered early in the history of Tin Pan Alley that the song's cover played a most important role in the selling of the popular music sheet. From the mid-1890s, publishers took great care with their covers. Sometimes a combination of photograph and illustration was used; sometimes a performer's photograph appeared on the cover. A performer's photograph on a cover served as an incentive for the performer to retain the song and to encourage fans of the performer to buy the sheet as a souvenir. Whatever the motivation, by the turn of the century cover art was a significant element in helping to sell copies of sheet music. Today these covers often comprise the only extant photographs of some of the places and people of this era, giving the covers added desirability, importance and value.

Along with getting a star to use a song in the act or on the air, publishers discovered early in the history of Tin Pan Alley that the song's cover played a most important role in the selling of the popular music sheet. From the mid-1890s, publishers took great care with their covers. Sometimes a combination of photograph and illustration was used; sometimes a performer's photograph appeared on the cover. A performer's photograph on a cover served as an incentive for the performer to retain the song and to encourage fans of the performer to buy the sheet as a souvenir. Whatever the motivation, by the turn of the century cover art was a significant element in helping to sell copies of sheet music. Today these covers often comprise the only extant photographs of some of the places and people of this era, giving the covers added desirability, importance and value.