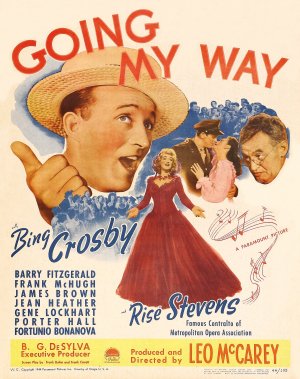

Start with the Crosby image of Father O'Malley. We first see him seeking directions to Saint Dominic's Church in black clericals and a straw boater. A peculiar combination of religious restraint and jauntiness which perfectly defines the developed character. It turns out that Father Chuck worked out with the Saint Louis Browns and led a small scat band in his previous existence. He may be a priest, but he is a real OK guy. There is even "romance." In a later scene an old flame, played by Rise Stevens, invites him to her dressing room at the Metropolitan Opera. While dressing in the adjoining room she asks through the open doorway why he had never answered her letters, "You wrote to me in Rome, Florence, in Naples, Vienna, Budapest ... From there I went to South America. There were no more letters. What happened Chuck?..." As it happens, Chuck has been wrapped in a raincoat up to now so that Ms. Stevens has not seen the clerical collar. She emerges from the dressing room: "What happened Chuck? What hap--." She sees the Roman collar, beams in surprise, "Father Chuck!" Father Chuck knows all the American ways of sports, jazz, and romance--but from another life.

Father Chuck's actions in the film express a sort of magical priestliness as he solves every problem great and small from the finances of Saint Dominic's to street gangs. The problems are solved in disguise, as it were, just as the straw boater disguises his true priestly power. Novelist and critic Mary Gordon writes:

Father O'Malley's great gift is to see everyone's need and provide for it. He is infinitely flexible, infinitely equipped with resources. He's both the ideal father and the ideal mother, nurturing yet with access to power, particularly in the sacred American precincts of show business and sports. Although his aura is maternal, his identity is necessarily and inextricably connected to maleness.... His maleness is iconic, but it is a particular kind of maleness cut off from the implications of sexual demand.

Desexualized power, the iconic male capacity to fix things as if it were all improvised on the spot, lucky accident, a spot of grace, expressed in the nonchalant manner of the Groaner, Der Bingle. In the sequel film, Bells of Saint Mary's, Father Chuck reassures a distraught Sister Ingrid Bergman that when in trouble she need only dial "O" for O'Malley. Mary Gordon reports on a priest friend who claimed that for generations, Father Bing was the paradigm for priests. So be it for the "golden oldies," but I suspect that somewhere in the passing years, Father Chuck's line has been disconnected.

It is not just the magical power of Father Chuck that attracts. Consider the message in the music written for the film by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Huesen. All the songs are songs of aspiration, cultural uplift, and deferred gratification. The Academy Award winning Swinging on a Star is sung by a street gang converted into the Saint Dominic's choir. The point of the song is that if you don't go to school, you may grow up to be a mule. On the other hand, attention to the books, and you "could be swinging on a star." If you are "going my way" "...this road leads to "rainbowville." Gratification is deferred -- "happiness is down the line."

The most interesting message for this priestly story is in the first song of the film. The local very Irish cop brings to the rectory a young girl who has run away from home. The cop is afraid that she may end up, ahem!, on the streets. The girl tells Crosby that she will make it on her own as a singer. Father Chuck offers to give her a tryout to his accompaniment. The girl sings the song with some awkward "jazzy" gestures. Father Bing tells her to put heart into the song and he shows her how. The song reads, "The day after forever / All through a lifetime / I'll be loving you / And on the day after forever / I'll begin again."

Again the dominant theme of gratification deferred. Just as Father Chuck's "romantic life" is elsewhere in another time and place, so fulfillment is elsewhere: Take a short cut to what you wish and you may end up as a fish, happiness is down the line, and love is not just today, it is "the day after forever." So, if you are going my way, the destination is tomorrow, not today.

The songs in Going My Way are in no way idiosyncratic; they are wholly within the Tin Pan Alley tradition which dominated American popular music down to the revolution of rock 'n' roll. Briefly put, Tin Pan Alley's great composers, often Jewish immigrants trained in traditions of European operetta, wrote music of cultural aspiration and deferred gratification.

If deferred gratification, cultural uplift, and commitment to the day after forever are the metaphysics of Tin Pan Alley and the theme song of Going Father Chuck's Way, all this changes radically for contemporary rock culture. Happiness is not "down the line," in the words of two best-selling albums of the Rolling Stones, it is Satisfaction and Now. A lyric by Robert Hunter, one of the principal writers for the legendary band The Grateful Dead, states the themes of rock. The song is called "Aim at the Heart" and the message seems the very antithesis of "the day after forever":

Time doesn't fly Just hangs over like the sky It's we who go by Makes no difference how or why Everything you cherish Throws you over in the end Thorns will grab your ankles From the gardens that you tend Damned if you do Double damned if you don't try Caught on the fly Hello fades into good-by What can you say? Here tomorrow, gone today Faith fades away For idols with their feet of clay

The chorus is: "Aim at the heart / Don't ask whose love you're stealing." I am certain that swinging Father Chuck would be horrified by the theme of Robert Hunter's lyrics. Hunter's world is as fragile and transient as the title of his 372 pages of collected lyrics, A Box of Rain (Viking Penguin).

Plato says in The Republic that changes in musical style indicate profound changes in the culture. For this reason he is determined to prevent of the Lydian mode into his ideal state. Rock music broadly conceived is one of those radical changes in musical style that deserves notice for what it promotes -- especially what it might promise or deny to religious sensibility. What does rock culture suggest: a new religion, an emotional collectivism which will rule the world (Peter Townshend of Who), or "overblown nonsense" (Mick Jagger)?

It seems clear enough from title alone that Going My Way and Fleetwood Mac's "Go Your Own Way" inhabit different emotional territories. Everyone has listened to enough rock -- willingly or not -- to have some idea of the musical character of such songs. Clearly this is not Crosby crooning "the day after forever." It is, as music critic Greil Marcus has written, "an assault, a hammering ... moaning, pleading, damning...."

The religious question I want to ask is contained symbolically in Marcus's description of the music. It is, he says, rough, harsh, hard to follow." As spiritual advice, is "going your own way" rough, harsh, a prescription hard to follow? Does "going your own way" lead to traumas and tragedies well beyond the gentle comic life of "going Father Chuck's way" where the burden is easy and the yoke is light?

Sam Phillips, the legendary producer of Sun records out of Memphis, the discoverer of Elvis Presley, characterized rock as the music of disillusion -- "the passion of a moment that was meaningless." Jimi Hendrix stated its metaphysic: "I am what I feel." If, as Robert Hunter says, "Faith fades away / for idols with their feet of clay," life is something "caught on the fly."

On its face, it would seem that rock is not only distant from the Saint Dominic's of Father O'Malley but from the saint himself and the dominant Christian tradition. One could dismiss rock as mere paganism all over again. But if old paganism became new gospel, maybe there is something in the new Eleusinian mysteries worth recapturing for the Old Time Religion.

In Marcus's description of "Go Your Own Way," he tries to explain why an instrumental solo, normally a "rest" in the performance, is suddenly a burst of even greater energy:

Building in any successful rock 'n' roll record is a sense of the power of the singer to say what he or she means, but also a realization that the words are inadequate to that task, and the feeling of fulfillment is never as strong as the feeling of frustration .... The singer still comes up short; the performance demands the absolute lucidity it has already promised ... and so an instrument takes over. It is a relief, a relief from the failure of language. The thrill is that of entering a world where anything can be said, even if no one can know what it means.Having described how music finally transcends verbal message, Marcus goes on to discuss a hokey song called "(What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love and Understanding," as performed by English rocker Elvis Costello with some simple, nonsinging, chord changes on his guitar.

Not only is the built-in hokiness of the tune diverted, the irony is boiled off; the guitar notes don't neutralize the pathos of the lyrics, they validate it. What's so funny about peace, love, and understanding? Now, nothing. For an instant, the search for peace, love and understanding is what life is all about. You come back into the ordinary world, the world of ordinary language, with a wonderful story: "I saw it! I heard it!" "What was it?" everyone asks, and you open your mouth, and begin to wave your hands in the air.

Imagine the Apostles preaching on the street corner, certain that peace, love, and understanding is what life is all about. "I saw it! I heard it!" Someone begins to write it out: the New Testament with lyrics by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. But suppose the original experience was validated where language broke down, and some elemental music of life allowed one to believe that even after an experience of defeat, betrayal, and death, "peace, love and understanding" is what life is all about.

Traditional Christian theology argued that the noble Greek virtues -- courage, temperance, justice -- were, after all, only "splendid vices" in comparison to the distinctly Christian virtues of faith, hope, and love. This is a defensible claim only if the life of the spirit is our fundamental human reality. The theologian John Dunne, in Time & Myth (University of Notre Dame Press, 1975), traces the life of the spirit in Dante's journey from Hell to Paradise. The stages of that journey reflect the basic possibilities of spirit. Somewhat revising Luther's characterization: Hell is despair; Purgatory is hope; Heaven is certainty. Spirit contains the fundamental "mood" of life.

The traditional moral virtues may have their place, but for the Christian the fundamental issue is whether they dwell within the spirit of despair, hope, or certainty. Macbeth despairs: life is "a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing" but for all that, he is courageous. One may dispense justice as a futile gesture of despair, or with a certainty that the heavens rejoice in the doings of the just. Because despair, hope, certainty lie behind the acts of every day, setting the tone if not content of life, we can, as it were, fail to notice them; we fail to recognize the life of the spirit.

Because the life of the spirit, the mood and music of life, is so fundamental, we properly label it as "mystery." I mean by mystery not something hidden from knowledge, like the cure for AIDS, but something so revealed, so present, that we cannot distance ourselves sufficiently for proper appraisal. Gabriel Marcel defines mystery as "a problem which encroaches on its own data." Assessing my spiritual state fits that description, am I hopeful examining my hope?

The contrast between Tin Pan Alley's Going My Way and the rock experience of "Go Your Own Way" is a contrast between morality and mystery. Going My Way as movie and song moves in the world defined by morality. Will stingy banker Gene Lockhart relent on the mortgage to the church? Sexual morality as sexual restraint is a central issue in the celibate state of the priests and the temptations of the runaway and her boyfriend. Father Chuck is ultimately a moral magician who shows everybody that if you don't care a feather or a fig, you may grow up to be a pig. He is magical because conversion to proper conduct requires only a slight symbolic gesture. Since there is little enough morality these days to go around, I am not going to knock it no matter how it is achieved, but I do want to say a good word for mystery.

Sexual restraint is central to Going My Way not only as a good in itself and a sign of priestliness, but as the most striking example of gratification deferred in the formation of moral character. Post the rock revolution, sexuality is flaunted; "don't care a feather or a fig!" A morality of deferred gratification appears to put off the real me to another day, but I can't really postpone my life. No wonder that rock appeals to teenagers, a stage on life's way when one seems to be full grown, yet stuck in a nest of economic and social deferrals and dependencies. Enter rock music as a statement of fullness now! The adoption of animal names for Rock groups--Eagles, Beatles, etc.--is not accidental. Animals, unlike humans, lack future pretensions; there are no fish striving to be archbishops. Animals are all in all, just what they are; it is this "fullness of being" which rock seeks to recover.

Rock reminds critic Camille Paglia of the great mystery religions. It is mystery even on its surface. Tin Pan Alley types like myself complain that they can't understand the words. But that is the point; like the cries and shouts of the Bacchantes, these noises suggest more than they can say until finally even the words give out and the crash of sound prevails. Rudolph Otto described the holy as mysterium, tremendum, et fascinans: a good description of a major rock event. The sound and the effects are tremendous and fascinating. The mystery evoked is a self, the Whatever-It-Is that is "going your own way." The rock n' roll self is not the moral self which is always beyond itself, deferring the present for the future, weighing and assessing the course of action. The rocker's self is the whole present reality, the very feel of present existence.

If sexual deferral is an important symbol for the music of morality, flaunting sexuality is an important symbol for the mystery in rock 'n' roll. Whatever else one might say about sex, it is an overwhelming experience of presentness. One of the reasons that moralists are so suspicious of sex is its ability to waylay the distancing and appraisive stance which is required for moral effort. Rock aims to get moral appraisal out of the way: Elvis Presley starts off the rock revolution on the proper note with his first big hit, "It's All Right, Momma!" Momma's moral injunctions are put aside.

I would like to propose a proper synthesis of morality and mystery, but the exact synthesis eludes me. My initial sympathy is with the rockers. I am inclined to believe that the spiritual journey is "rough, harsh, hard to follow," and that Father Chuck's world is only charming fantasy. In the long run--and the short run--you have to "go your own way." As the old black spiritual puts it: "You got to walk that lonesome valley by yourself; ain't nobody here gonna walk it for you...." There is something fundamentally out of kilter in a view which translates Christianity into nothing but moral injunction. I tell you the story of Christianity: a zealous peasant preaches a message of mercy and forgiveness, he is betrayed, abandoned, tortured, and put to a cruel and horrible death only to rise above death through God's almighty hand--and by the way, he didn't approve of premarital sex. I fear that this is the religious distillation of Going My Way and all too many traditional Sunday sermons.

Rock with all its excesses has the advantage of inhabiting spiritual territory, a territory where despair and hope, absolute loneliness and transcending love can abide. It is easier to think of converting a sexually passionate Augustine to burning Christian belief, than turning Father Chuck into Saint John of the Cross.

But if rock opens into the life of the spirit, while O'Malley's moral musical messages do not, one has to assess the spiritual life expressed. There is certainly a strong current within rock of Sam Phillips's "disillusion." Death, like sex and drugs and the rocker's scream, accomplishes the fullness of being-there is nothing yet to come.

If that is the final message of the music, it is certainly unacceptable to Christian belief. Nevertheless, rejecting the rocker's world is not easy. The disillusion and despair which are everywhere expressed in the music only make sense in a world of hope and love denied. In the back of the minds of the most disillusioning rock tune is a belief that "peace, love and understanding" is the real meaning of life. The problem seems that there is no known way of getting there. Except for the music itself.

Except for the music itself: in the mystery which is at the center of the spirit, there is a paradox within anyone who creates and crashes out a great hymn of despair. The lyric says despair," but the music can transcend despair in its very boldness and assertion. W.B. Yeats says that Lear is "gay" in the very depth of his suffering.

Finally, rock can only believe in artistic enactment; Christianity makes the bolder claim about reality. You can call yourself an Eagle, Door, or Stone, but one remains, alas, merely human. Humans have to work themselves up (or down) to the fullness of animal intensity, but the moment passes until the next dose or drum beat. Sexuality may be a symbol of fullness, but, unfortunately, humans cannot live in the innocence of animal sexuality. The fullness has to be human sexuality. Humans finally have to deal with the fact that the sexual other is a person--a category which transcends animal structures and the only one which validates a quest for peace, love, and understanding.

The story of Jesus claims that actual human life, not the bold artifice of rock, can express the fullness of being. The rock impulse recognizes the superiority of the world of the spirit, but finally there is no incarnation, no daily bread. The spirit is reached only outside ordinary daily life in drugs, ecstatic sex, overwhelming music. One longs for a world of peace and love, but there is no assurance that it can exist anywhere except in the right riff and set of chord changes. Finally, rock is an aesthetic passing as religion--not the first or last time that noble gesture has been tried!

T.S. Eliot, who of course knew nothing of rock 'n' roll, expresses in The Four Quartets a view which might encapsulate a Christian response to this music.

For most of us, there is only the unattended

Moment, the moment in and out of time,

The distraction fit, lost in a shaft of sunlight,

The wild thyme unseen, or winter lightning,

Or the waterfall, or music heard so deeply

That it is not heard at all, and you are the music

While the music lasts.

... The rest

Is prayer, observance, discipline, thought, and action.

Lacking incarnation, the spiritual world of some to-be-named

rock group, Wild Thyme, cannot move to "prayer,

observance, discipline, thought, and action."

How to resolve the dilemma presented by Going My [Moral] Way and "Go Your Own Way" As I read the gospel message, "Go Your Own Way" remains fundamental in the sense of that black gospel hymn. Each person lives and dies the one life that is his or hers alone. There is a fundamental aloneness to being human; an aloneness that makes the animal warmth of sex and heavy metal a seductive anodyne. It also makes the moral message of O'Malley seductive. I lose myself in moral earnestness. That may be a better path in so far as morality is a distinctively human trait. Chastity as a symbol of human freedom is better than sex as an ardent retreat from care. But common morality cannot be used as a shield for the aloneness of the spirit. Mary Gordon concludes her account of Father Chuck as follows:

[Father Chuck's] maleness is iconic, but it is a particular kind of maleness cut off from the implications of sexual demand. It is part of his vocation to make no demands, so he gives no ground, no place for anyone to stand. There is no there with Father Chuck.If the final word is "Go Your Own Way," a way that is "harsh, rough, hard to follow," Christianity at least says that one is accompanied on that way. Jesus is not the absent moralist who sets out the road map for life; Jesus is the one who comes with, on the same journey, living his own story which ends in loneliness and abandon. Yet he goes forward, and he goes forward alongside the Christian believer, so that his story of resurrection and my story exist for one another. There is a there to Jesus which is not present in the clerical figure of Father Chuck. Jesus and the lone believer are spiritually open for one another. In one of her mystical experiences, Teresa of Avila hears the question, "Who are you?" "I am Teresa of Jesus," she answers, "and who are you?" "I am Jesus -- of Teresa."If there is no there to Father Chuck, what is missing is the aloneness of the spirit. If sexual fulfillment is a traditional symbol of spiritual fulfillment, sexual demand, then, can be a symbol of spiritual need. Antiseptically cleansed of sexual demand, Father Chuck becomes spiritually neutered.

The implications of the pop culture of rock music for churches are ambiguous. The New York Times ran a feature article "Rock Finds Religion Again" (January 2, 1994.) The author, Guy Garcia, noted an almost apocalyptic denunciation of empty materialism -- themes which have been stated in more measured terms by John Paul 11. But the "salvation" sought by a rock singer like Michael McDermott in his album Gethsemane is strictly personal, outside if not against the churches. In a song called Leave It up to the Angels," McDermott sounds the broad theme of disillusion that runs through rock: "I'm frightened by the way I feel, maybe you are too/I'm losing faith in everything and everyone but you ... leave it to the angels."

The implication for official Catholicism may be contained in McDermott's personal history. A former altar boy, he contemplated entering the priesthood but, he say, "[I am] too weak a person to ever be a priest." The ghost of the omnipotent, invulnerable Father Chuck haunts the church: far from an image of sympathy or salvation, he is--in rock idiom--a "real turnoff!" Only a narrative responsive to passion, loneliness, and defeat responds to the rocker's urge. The Gospels have such a narrative (though with a startling twist at the conclusion). A God so vulnerable may require vulnerable ministers of grace.