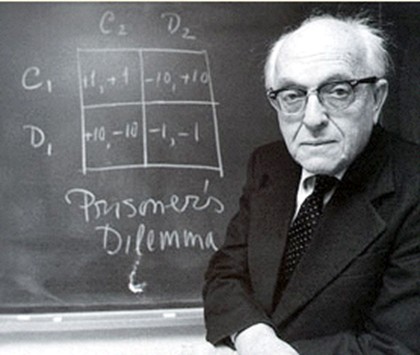

Anatol Rapoport

Written 2017 by Steven Lewis

Anatol Rapoport (1911-2007) had much in common with Korzybski, but the two never established a working relationship. Both were immigrants to the United States from Eastern Europe. Korzybski was born and raised in Russian-dominated Poland, Rapoport was born and raised in Russian-dominated Ukraine to Jewish parents. Both became polylingual pacifists and both developed a deep interest in mathematical "psycho-logics," a term Korzybski coined to merge psychology with what later became known in educational circles as "critical thinking." Following the communist takeover in Russia, the Rapoport family emigrated to the United States in 1921, settling in Chicago. Rapoport became an accomplished pianist, and returned to Europe in 1929 to pursue a musical career. When he returned to the United States 8 years later he decided to change career directions and enrolled in the University of Chicago, where he earned a doctorate in mathematics in 1941. It was at the University of Chicago in 1938 that Rapoport joined the Communist Party. After the United States entered World War II as allies of the Russians he quit the Party in order to join the armed forces, and was sent to Alaska to teach math and physics to aviation cadets. Rapoport stated that his committment to the Soviet Union reached it zenith during World War II. It wasn't until after the War that his enthusiasm waned, largely as a result of the Soviet perversion of science known as the Lysenko Affair (Rapoport, p103).

Although Korzybski's Institute was founded near the University of Chicago campus in 1938, Rapoport reported no knowledge of Korzybski or his work until a girl friend in Alaska loaned him a copy of Korzybski's Science and Sanity in 1943. Rapoport reported that he was turned off by Korzybski's verbosity and neologisms and dismissed the book as "pompous nonsense" (Rapoport, p3). Later, however, he reported finding an abandoned copy of S.I. Hayakawa's Language in Action, an English textbook based on Korzybski's General Semantics. This was a book he could comprehend, calling it "a miniature masterpiece." He wrote to Hayakawa, who was teaching at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, and included an account of his attempts to teach math and physics to aviation cadets. Hawakawa wrote back offering to publish Rapoport's paper in Etc, A Review of General Semantics, a new journal edited by Hayakawa and Korzybski. His report appeared in the spring 1944 issue of Etc. and was titled Newtonian Physics and Aviation Cadets and earned Korzybski's praise.

When Rapoport returned to Chicago on leave he attended a lecture by Korzybski at his Institute at 1234 East 56th Street. Rapoport wrote in his autobiography that he did not find Korzybski's lectures interesting or enlightening (Rapoport, page 80). Hayakawa invited him to Korzybski's office for a meeting. Rapoport reported that Korzybski's first words to him were "You have read Science and Sanity ... how many times?" In fact, Rapoport did not own a copy of Korzybski's book and had never read it front to back even once, but he avoided the whole truth by saying he had re-read some passages. Following the war Rapoport took a teaching job at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago and joined the editorial staff of Etc. Korzybski grew increasingly distraught by the dilution and representation of his work in Etc, resigned as consulting editor and moved his Institute from Chicago to Connecticut, where he began his own periodical, the General Semantics Bulletin.

When Rapoport completed his first book, Science and the Goals of Man, he asked Korzybski to write a recommendation for the publisher. But when Korzybski read the galley proofs he refused an endorsement. Korzybski died in 1950 shortly before the book was published.

In his autobiography Rapoport listed Hayakawa, but not Korzybski, as one of his three principal mentors, although Hayakawa was merely a lucid popularizer of Korzybski's formulations. He said that Hayakawa's presentation of Korzybski's work "clarified the basic ideas in Korzybski's magnum opus ... retaining their full strength but trimming away the author's narcissistic posturing and obscure verbiage." (Rapoport, p3) Although he viewed Korzybski as eccentric and verbose, Rapoport stated in his autobiography that he did not consider Korzybski a "crank," unlike some in academia. (Rapoport, p79)

Their similar origins, interests and capabilities suggest Rapoport and Korzybski should have had a more empathetic relationship. 'On paper' Rapoport would seem to be the most likely to succeed Korzybski. It didn't happen that way, however. To Rapoport, as to many others, Korzybski was a strange visitor from another planet. But Rapoport came to the United States when he was 11. Korzybski arrived from Eastern Europe when he was 36. In many ways Korzybski was more Polish than American. Rapoport was traditionally educated, eventually earning a doctorate from the University of Chicago in mathematics. Korzybski was largely privately schooled and self-educated. Korzybski's rich Polish accent made him difficult to understand. His hearing impairment made it difficult for him to understand others. His war injuries made it difficult for him to walk. His uninhibited speech, shaved head, khaki dress and use of toilet paper as Kleenex offended some and frightened Mrs. Hayakawa. His intolerance of the limitations and deviations of his popularizers resembled the behavior of a helicopter parent. Einstein was never as possessive of his relativity theories as Korzybski was of his General Semantics. In short, in many ways Korzybski did not apply his own principles. Had he done so he would have behaved in a manner less likely to alienate those who could be of most help to him. That includes his relationship with Rapoport and Hayakawa. The fault was not entirely theirs.

Quoting Korzybski:

... understanding of the shortcomings of others has an important semantic, broadening effect. In life, numerous serious 'hurts' occur precisely because we do not appreciate some natural short-comings and expect too much. Expecting too much leads to very harmful semantic shocks, disappointments, suspicions, fears, hopelessness, helplessness, pessimism,. (Science and Sanity, p472)

Rapoport's frustration trying to comprehend Science and Sanity most likely has been felt by all its readers, this author included. Much of this frustration stems from the depth and breadth of subject about which Korzybski was communicating. But the "neologisms" about which Rapoport complained including "psycho-logics," "abstracting," "multi-ordinality," "semantic reactions," "time-binding," "dynamic structure" ... imply the meanings necessary to convey Korzybski's message. Hayakawa uses most of these same terms in Language in Action, where they seemed to cause no problems for Rapoport. Perhaps what Rapoport really meant was that he was frustrated by Korzybski's frequent field trips into molecular biology, neurology, quantum mechanics, relativity ... to illustrate the origins and applications of his theory. What is often ignored by Korzybski's literary critics is that he learned to read and speak English less than 20 years before producing his 800-page treatise in English on the foundations of science and mathematical behavior. From this perspective alone Science and Sanity is a remarkable accomplishment. The cup that is half empty is also half full.

Hayakawa and Rapoport remained friends and co-editors of Etc. into the 1960s. Rapoport met his future wife at a gathering at Hayakawa's home in 1947. Nevertheless, like Korzybski, Rapoport eventually had a falling out with Hayakawa. The precipitating issue was Hayakawa's support of the Vietnam War. Rapoport's opposition to the war led him to resign his professorship at the University of Michigan and move to Canada in 1970, where he taught at the University of Toronto until retiring in 1976.

References:

Rapoport, Anatol. Certainties and Doubts -- A Philosophy of Life. Black Rose Books, 2000.

Paul, Derek. Anatol Rapoport, A Tribute. Science for Peace Bulletin Special Issue, Winter 2007.

General Semantics books by Anatol Rapoport:

Science and the Goals of Man (1950)

Operational Philosophy -- Integrating Knowledge and Action (1953)

Fights, Games and Debates (1961)

Conflict in Man-Made Environment (1974)

Semantics (1975)

Go to General Semantics Home Page ||| Go to Steven Lewis Home Page