That quality gave him charisma while marking him as a lightweight, made him seem absurdly passe by the mid-'70s while giving him a weird, nearly existential purity in his final decades. Slackers may be sipping martinis and neo-hipsters like Greg Mangus might be singing Martinesquely, but there was no Bennett-style comeback for Martin; in fact, he sourly bailed out of a 1988 reunion tour with Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. after hollering "I wanna go home!" from the stage and flicking a lit cigarette butt into the audience. His ex-wife Jeanne, to whom he was married for 23 years, once sighed, "There's either nothing under there or too much." Nick Tosches' 1992 biography, Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams, calls him a menefreghista, Italian for "one who simply does not give a f---."

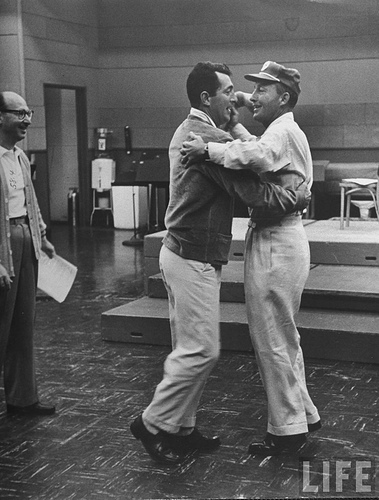

Born Dino Paul Crocetti on June 17, 1917, Martin grew up the son of an immigrant barber in Steubenville, Ohio. He worshiped at the altar of Bing Crosby and made a go at a singing career, mutating from Dino Crocetti to Dino Martini to Dean Martin, and picking up a new nose in the process. In 1946, he and a lantern-jawed comedian named Jerry Lewis began kibitzing in on each other's acts; by the time the duo played Slapsie Maxie's in Los Angeles two years later, they had the industry in their palms.

Sixteen hugely popular Martin and Lewis films followed in seven years, and as the comedian's ambitions ballooned, Martin simmered, despite having a successful recording career on Capitol that crested with the 1953 top hit "That's Amore." By 1956, tired of breakups and makeups with the insecure Lewis, Martin told him, "You can talk about love all you want. To me, you're nothing but a f---ing dollar sign." And he was outta there, pally. Martin never looked back, rarely acknowledging Lewis' existence, while his ex-partner erupted in public outpourings of separation anxiety. (Lewis was too "shattered by grief" to comment on Martin's death, according to Lewis' manager.)

No one thought Martin would make it on his own. Reviews for his first solo film, Ten Thousand Bedrooms, were brutal ("Apart [from Lewis], Mr. Martin is a fellow with little humor and a modicum of charm," said The New York Times). But Martin's ensuing choices were inspired: a GI in The Young Lions opposite Brando, an alcoholic deputy (his best dramatic role) in Rio Bravo.

Then the Rat Pack came calling, offering the position of Frankie Lite alongside Sinatra, Davis, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop in movies and Vegas nightclubs. To make his allegiance clear, Martin left Capitol to record on, and financially back, Sinatra's Reprise Records. His apotheosis came in 1964: "Everybody Loves Somebody" knocked the Beatles out of the No. 1 spot, and he starred in Billy Wilder's Kiss Me, Stupid, which epitomized Martin's persona as a lovable, lecherous lush. Condemned by critics and the Catholic Legion of Decency, Stupid was the Showgirls of its day, yet its acrid playboy nihilism may be the closest he came to a personal statement.

The next year saw the debut of The Dean Martin Show, a variety program that ran for nine successful seasons on NBC. Yet pop culture was shifting away from him: The show's va-va-voom chorus line, the Golddiggers, caused the National Organization for Women to give Martin a Keep-Her-in-Her-Place award during the final season. The Matt Helm spy spoof series that began promisingly with 1966's The Silencers quickly ran aground with three limp follow-ups. His records veered toward workaday country; Martin would lay down vocals only after producer Jimmy Bowen had recorded all the other tracks.

The late '70s and '80s saw Martin slope off into halfhearted singing gigs and celebrity roasts featuring the likes of Milton Berle and Foster Brooks--Last Suppers for the borscht belt. After his son Dino Jr., 35, died in a 1987 plane crash, Martin seemed to vanish into himself. He haunted Hollywood restaurants, alone, with an ever-present drink in his hand. "I'm just waiting to die," Paul Anka says Martin told him one night.

But that tragic vision doesn't square. Tragedy necessitates self-knowledge, and indications are that Dean Martin rolled blissfully on the waves of unthinking fortune to the end of his days. "He had no interest in his own life," says biographer Tosches. "He was completely content in his solitude. I wanted him to hit 80. That was the age that Buddha was when he died. I kind of thought of him as an American Buddha."